The first phase of the Leveson inquiry in the British press isn’t quite finished yet, but the inquiry is entering new territory. Or at least there’s a change of mood.

The opening weeks were dominated by complaints and horror stories about red-top reporters. Straws passing on the wind tell me that this indignation is now being replaced by more sober reflection about the issues which face big-circulation papers.

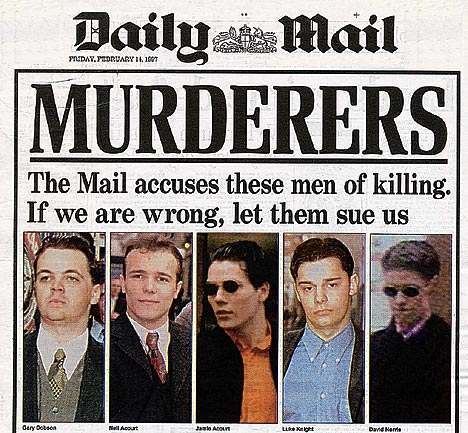

Daily Mail February 1997

Here are the straws I’ve counted recently. Lord Leveson himself has from the start been keen to underline that he is not embarking on any project to “beat down” popular papers. He has also been asking each of his celebrity witnesses what they would do about the faults of which they complain and has more than once sounded a little irritated by the vagueness of the prescriptions he is offered. When editors take the stand at Leveson this month, we will be reminded that popular journalism can reveal important truths and explain complex events in ways that papers with bigger reputations and much smaller circulations can’t manage. Jonathan Freedland of The Guardian, at one time a columnist for the Daily Mirror, wrote a defence of the tabloids the other day.

The conviction of two men for the 18-year-old murder of Stephen Lawrence has reminded the country that the case was kept alive by one of the more extraordinary editorial gambles of its era: a front page of the Daily Mail in 1997 which accused five men of the murder. The Mail is the paper many love to hate, but its editor Paul Dacre played a fine part in the dispiriting Lawrence saga by putting his job on the line with that campaign. (It seems improbable that the Mail had courtroom-standard proof of the mens’ guilt when it published, so if they had sued and won Dacre could not have survived in his job).

Inquiries work at multiple levels before they ever recommend anything. The mere existence of the Leveson Inquiry has forced people to think about law, regulation and press freedom in depth. It has legitimised criticism of the media which, apparently, politicians were too terrified to make. The very varied reactions to the inquiry so far are on show at this panel discussion last night at the Frontline Club (video here and shorter versions here and here).

A very good illustration of the knotty problems was given in that discussion by Ben Fenton of the Financial Times. The problems of popular paper newsrooms, he said, could be summed up in the phrase often used to reporters by editors: “make the story work”. There’s a benign use of this instruction, as in “make this work better for the reader”. But that isn’t the usual sense of “make it work”. Those words now mean: we’ve already told you what the story is – now find material which backs it up. There are a hundred different reasons why this gradual corruption of the idea of what a story is or should be has taken place, many of them to do with ferocious competition between papers. Every journalist has to balance impact against details of the truth. But in some newsrooms, “making the story work” has been at the root of a lot of distortion and dishonesty.

Ben’s example was well chosen. But can you legislate or regulate to put that right?

Tags: Ben Fenton, Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, Financial Times, Jonathan Freedland, Leveson Inquiry, Paul Dacre, The Guardian